I'm in Oxford, at the Oxford Internet Institute, for Trinity Term. (More photos coming soon and at flickr.)

I'm in Oxford, at the Oxford Internet Institute, for Trinity Term. (More photos coming soon and at flickr.)

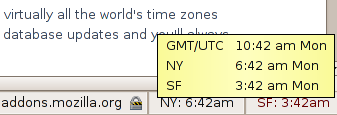

Among email, web, and skype, I can stay in pretty close touch with the U.S. -- so long as I know when it is. FoxClocks is a handy little Firefox plugin that puts a multi-time-zone clock into the Firefox or Thunderbird status bar.

Several people I talked to about the NFL copyright warning reminded me that Major League Baseball goes even further off the wall with its assertions. I grabbed a couple of local games last weekend and here present a comparison of the copyright warnings from the Yankees (via Fox) and the Mets (via CW11).

This copyrighted telecast is presented by authority of the Office of the Commissioner of Baseball [or Sterling Mets]. It may not be reproduced or retransmitted in any form, and the accounts and descriptions of this game may not be disseminated, without the express written consent [of Sterling Mets].

I have included no "accounts or descriptions of the game." In each clip, I tried to capture the warning plus a bit of the broadcast's context. In each case, YouTube chooses a screenshot from near the end, after the warning. Will MLB's copyright bots drop the ball? What's your favorite sports copyright claim?

Today, 12 business days after I re-sent my DMCA counter-notification, YouTube sent notice that they had restored my Super Bowl excerpt. Catch it while you can, because I'm not holding my breath that it will stay online this time either.

The chronology so far:

By my count, that's 17 days up, 38 days down, not counting "technical problems" that prevented access to the video on some days when it was not sidelined by a notification.

In the first takedown first DMCA takedown NFL sent YouTube in February, shortly after the Super Bowl, my video of the copyright warning was among 162 URLs listed. After YouTube re-posted my video, NFL's second DMCA notice singled out just one video, the one for which I had counter-notified on fair use grounds. If there was any excuse that the first claim was just a bot's overactive pattern-matching -- an excuse the NFL doesn't rely on in its response on the Wall Street Journal's Law Blog -- that excuse evaporated by the time I counter-notified.

Rather, NFL Spokesman Brian McCarthy argues,

We are entitled to disagree, in good faith, with her asserted defense, absent a court decision.

(3) We have valid grounds to disagree with the professor’s fair use argument. Had she simply used the clip in her classroom, before students, she might have had a stronger argument that the context was educational and entitled to fair use deference. But it was posted without any of this context, and in a manner available for anyone in the world to see, not just her students.

I think their fair use analysis is wrong as a matter of law, and therefore it was “knowingly materially misrepresenting” to claim that the clip infringed after getting notification of the clip’s content. I’m entitled to share this type of educational fair use with more than the students in my classroom. (I’m not trying to rely on the TEACH Act with its crabbed DRM requirements.) I post my syllabus and teaching slides online for anyone to see, and wanted to post this discussion similarly.

On the fair use factors, I think I’m in good shape: My use is for nonprofit educational purposes; the copyright in the telecast is thin; the portion of football that follows the copyright warning is a minute portion of the whole, with no significant action or commentary, useful to show people what it was the NFL claimed its copyright covered; and the effect on the market for or value of the work is non-existent.

Too bad the U.S.'s WTO non-compliant gambling law prevents us from wagering on what will happen next...

I had to double- and triple-check the dateline on this press release, not because it's foolish, but because it is so far from what we've heard the near-unanimous record labels saying for so long. But the dateline is April 2, so that must mean that EMI really is launching DRM-free superior sound quality downloads across its entire digital repertoire:

London, 2 April 2007 -- EMI Music today announced that it is launching new premium downloads for retail on a global basis, making all of its digital repertoire available at a much higher sound quality than existing downloads and free of digital rights management (DRM) restrictions.

According to the announcement, in May EMI will make its catalogue available on the iTunes music store in 256 kbps unencrypted AAC files at $1.29 per track. That's double the bitrate and free from digital rights management, as compared to the standard DRM-encumbered iTunes offerings at $.99-per-track.

What does this mean for music fans and copyright watchers? For music fans, it's another option that is better than previously available EMI downloads on two axes: higher sound quality and better interoperability. At twice the bitrate, you'll hear fewer compression artifacts. The unencrypted AAC files will play on any device that supports AAC, unlike the FairPlay-burdened iTunes files that play only on iPods and iTunes computers that have authorized to the Apple mothership. If your device doesn't support AAC, iTunes offers to convert to MP3. That means you can take authorized downloads to your Squeezebox or GNU/Linux PC. You can still get higher quality, more interoperable files by ripping your own from CD, but without the right-away convenience of downloads.

For the copyright-watcher, the move suggests that EMI management is cooling to the standard "piracy" line for DRM and the claim that it "keeps honest people honest." They've seen that DRM'd tracks end up fileshared just as quickly, while inconveniencing the honest users who want to move beyond the iPod. Moreover, they've seen the chief effect of DRM has been to lock both listeners and record labels to Apple's sales chain, since only Apple offers FairPlay and no other DRM plays on the popular iPod. Perhaps EMI recognizes its music is most valuable if listeners can choose their own playback technologies, rather than being restricted to the complements EMI determines and licenses. It also means that Apple has been willing to walk Steve Jobs's talk:

The third alternative is to abolish DRMs entirely. Imagine a world where every online store sells DRM-free music encoded in open licensable formats. In such a world, any player can play music purchased from any store, and any store can sell music which is playable on all players. This is clearly the best alternative for consumers, and Apple would embrace it in a heartbeat.

At the same time, EMI has put a lot of variables into its experiment, as Ed Felten notes. Will people be willing to pay more for unencumbered tunes? Will they be doing so for the lack of DRM or the higher sound quality? Will they be pleased or puzzled by the dual pricing structure, as DRM-laden EMI tracks will still be available for $.99? Were the players spooked by European antitrust investigators? It may be some time before we can analyze the whole picture, but this DRM rollback is a promising start.