ICANN's thrice-annual junket is concluding in Lisbon. I haven't been there, so I've been reading between the lines of the flurry of self-congratulatory press releases and announcements.

We learn, for example, that "Thousands of Voices Get Direct Say At ICANN," in a release that never discloses that no one's listening to this "say." Three new Regional At-Large Organizations have been formed, but not one of them allows individuals to participate directly, and not one of them has a voting representative on the ICANN Board or GNSO Council. We'll see if there's any room to address these questions in the ALAC review.

We learn also that the Board has, for a third time, rejected the .xxx TLD application from ICM registry. Will it stick this time? Will ICM litigate? Susan Crawford's vigorous dissent skewers ICANN's process and the legitimacy of its conclusions:

I must dissent from this resolution, which is not only weak but unprincipled. I'm troubled by the path the board has followed on this issue since I joined the board in December of 2005. I'd like to make two points. First, ICANN only creates problems for itself when it acts in an ad hoc fashion in response to political pressures. Second, ICANN should take itself seriously, as a private governanced institution with a limited mandate and should resist efforts by governments to veto what it does.

...

As a board, we cannot speak as elected representatives of the global Internet community because we have not allowed elections for board members. This application does not present any difficult technical questions, and even if it did, we do not, as a group, claim to have special technical expertise.

I've never thought .xxx was a good idea, but I've thought even more strongly that ICANN shouldn't be in the business of judging "good ideas" or making content-based judgments about new gTLDs. ICM jumped through the procedural hoops ICANN set, would not cause technical problems in the root, and so should be entitled to its domain.

Together, these developments show what a monster ICANN's web of contracts has created: a private regulator of public conduct with no public oversight. Watch out for the California public benefit corporation law, though...

I promise this blog won't become all-DMCA all the time, but as this saga gets more convoluted, it illustrates even better the problems with the law and with the various pressure groups' copyright demands. (See the complete set of NFL-DMCA posts.)

In apparent defiance of my counter-notification, the NFL sent YouTube another takedown notice, which YouTube followed with another takedown a few days ago, giving notice to me yesterday. Now when I sent my counter-notification to the first NFL notice, on February 14, YouTube forwarded it on to the NFL per the DMCA's specification. Since my counter-notification included a description of the clip, "an educational excerpt featuring the NFL's overreaching copyright warning aired during the Super Bowl," it put the NFL on clear notice of my fair use claim.

The DMCA way for NFL to challenge that, per 512(g)(2)(C), would be to "file[] an action seeking a court order to restrain the subscriber from engaging in infringing activity relating to the material," which they haven't. Sending a second notification that fails to acknowledge the fair use claims instead puts NFL into the 512(f)(1) category of "knowingly materially misrepresent[ing] ... that material or activity is infringing."

If the NFL deigned to respond, I expect they would argue something like "the volume of material is so high, we can't possibly keep track of all the claims of non-infringement. Our bots are entitled to a few mistakes." But if they're not able to keep track of the few counter-notifications they've received (the YouTube URL and page stayed the same at all times it's been up), how can they demand that YouTube respond accurately and expeditiously to all the DMCA notifications they send, or worse, filter all content as Viacom is demanding?

I have my complaints with the DMCA's notice-and-takedown regime, but where I think it goes too far toward chilling speech, Viacom thinks it doesn't go far enough. That's the gist of its recent complaint against YouTube. Viacom argues that despite YouTube's DMCA compliance, taking down videos when notified of copyright claims, the site should be held liable for direct and indirect infringement of Viacom's copyrighted works (specifically, public performance, public display, reproduction, inducement, contributory, and vicarious infringement -- what, no derivative works claim?).

Viacom is trying to renege on the bargain of the DMCA, in which copyright holders get pre-judicial injunctions against claimed infringement, and service providers are guaranteed immunity so long as they follow the takedown procedures. Viacom never alleges YouTube failed its side of the deal -- it doesn't point to a single un-complied-with takedown demand. Rather, it claims that requesting takedown is just too hard. Not content with a procedure that already strips away the free-expression protections of judicial oversight, Viacom wants to shift the burden to YouTube (and others like it) of preemptively filtering materials for possible copyright infringements.

Viacom is trying to renege on the bargain of the DMCA, in which copyright holders get pre-judicial injunctions against claimed infringement, and service providers are guaranteed immunity so long as they follow the takedown procedures. Viacom never alleges YouTube failed its side of the deal -- it doesn't point to a single un-complied-with takedown demand. Rather, it claims that requesting takedown is just too hard. Not content with a procedure that already strips away the free-expression protections of judicial oversight, Viacom wants to shift the burden to YouTube (and others like it) of preemptively filtering materials for possible copyright infringements.

Viacom's approach would have serious anti-innovation consequences. The DMCA gives hosting startups a predictable framework. (Note that YouTube succeeded as an independent startup where the established Google couldn't make Google Video popular.) Where hosts can't anticipate what users will post, they can nonetheless ensure against copyright liability by promising to take down material they're told is infringing, by any copyright claimant.

Viacom would instead have them negotiate first with (any? all?) copyright holders to install a pre-filtering system. Since automated filtering is far from perfect, this system would be both expensive and inaccurate. It would bankrupt the small startups and leave the larger ones open to the next lawsuit from a copyright holder who hadn't been consulted on the first filter. Google might be able to go down that road, but they'd be about the only ones. Viacom and friends would have veto power over any newcomers to the field.

Now that may well be what Viacom wants. That veto is what they got with another provision of the DMCA, the anticircumvention laws, but it's not what serves the public best. The safe-harbor bargain may be flawed, but Viacom's proposed alternative is worse.

I spoke with Marketplace about Google's announcement that it will anonymize search data after 18 to 24 months (FAQ). I'd like to see more, but I think that's a good start toward building competition around privacy policies.

Google recognizes, as many of us did after AOL Research made available a batch of user search queries, that aggregated searches can contain sensitive information. Even if we trust Google with that information, we don't necessarily trust everyone who might get it from Google.

As Ben Adida cleverly puts it, is your privacy safe even "if you include a subpoena as part of the threat model?" Last year, the government tried to subpoena bulk search queries for a fishing expedition into the availability of sexually explicit material. We know this because Google opposed the subpoena, while MSN, AOL, and Yahoo did not. We don't know how many other subpoenas search engines respond to unopposed, without notifying the target of the information search. It seems to me only a matter of time before lawyers in civil and criminal matters start requesting this information as part of routine discovery efforts.

After recognizing that the public senses a threat, Google's announcement also shows it's moved beyond the privacy afterthought's of its GMail launch to see privacy as a strategic opportunity. That means there's something to balance against the default convenience of storing information forever.

I heard a similar strategic view of privacy from Microsoft Counsel Ira Rubinstein, at the Berkman Center to talk about Microsoft's Privacy Guidelines for Developing Software Products and Services, a detailed guide to the potential privacy impact of programming practices published last year. The Guidelines note, for example, that use of a pseudonymous GUID rather than a name reduces but doesn't eliminate privacy concerns, since the GUID might still be linked back to a name later.

Microsoft says "These guidelines have been engrained in our development process and are now incorporated into the Security Development Lifecycle," and the privacy review Rubinstein described could add time and expense to product development. Microsoft hopes those costs will be repaid in user trust for the company and the industry.

I've never thought a market solution was the answer to everything. Yet one of the particular barriers to a functioning market for privacy has been lack of information. Individuals don't think through all the consequences of data aggregation, perhaps don't even know all the possibilities for its use and misuse. Their failure to demand much privacy gives suppliers little incentive to offer it. By announcing more rigorous privacy practices, Google and Microsoft may be trying to prime the market for their own services and software, but they're also doing a service to the public in helping us understand the information privacy risks. If we're committed to market solutions, let's at least help them function better.

Earlier in the Registerfly controversy, ICANN Vice President Paul Levins posted to the ICANN Blog,

Earlier in the Registerfly controversy, ICANN Vice President Paul Levins posted to the ICANN Blog,

ICANN is not a regulator. We rely mainly on contract law. We do not condone in any way whatsoever RegisterFly’s business practice and behaviour.

This is disingenuous. ICANN is the central link in a web of contracts that regulate the business of domain name allocation. ICANN has committed, as a public benefit corporation, to enforcing those contracts in the public interest. Domain name registrants, among others, rely on those contracts to establish a secure, stable environment for domain name registration and through that for online content location.

A user registers a domain name by contracting with a registrar, such as Registerfly. The terms of that agreement are constrained by ICANN's accreditation contract with the registrar. French registrar Gandi explains this web with helpful diagrams in its registration agreement:

Gandi is a Registrar, accredited by both the Trustee Authority [ICANN] and registry of each TLD to assign and manage domain names according to their specific TLD. We must abide by the terms and conditions of Our accreditation contract. As a consequence, We must pass some of Our obligations on to Our customers.

...

As such, We commit Ourselves to providing you with the best possible service. This being said, due to Our contractual obligations with the Trustee Authorities and Registries, and which You must also abide by, Our services are limited in some of their technical, legal, regulatory and contractual aspects.

Now the ICANN contracts can both limit and help the end-user registrant. On the limit side, they restrict the registrant's ability to maintain anonymity or privacy by requiring the registrar to provide accurate identifying information to the WHOIS database, a duty the registrar fulfills by compelling provision of accurate information in its own contract with the registrant. This requirement benefits trademark holders, who have recently turned out to prophesy doom if data display is limited.

On the benefit side, the RAA-imposed duty of data escrow, requiring the registrar to maintain an escrowed copy of its registration database, provides evidence of a registrant's domain name holdings in the event of registrar failure. Registrants seeing this provision could believe that their domain names would be secure even if the registrar who had recorded them defaulted.

So they might have believed, but apparently ICANN has never enforced this provision of its contracts. Moreover, ICANN denies that the public is a third-party beneficiary entitled to demand enforcement.

The Registerfly debacle shows why this view is wrong as a matter of law and policy. ICANN was told more than a year ago of customer service problems at Registerfly, but did nothing to respond to those complaints, including escrowing data, leaving the company's 200,000 registrants at risk of losing domain names or the ability to update them when Registerfly's business troubles escalated early this year.

ICANN should recognize that the reason for its registrar contracts is precisely to benefit third parties: domain name registrants and those who rely on the domain name system. ICANN is not (or shouldn't be) accrediting registrars merely to have a larger pool of organizations paying fealty to it. Rather, it is imposing terms and conditions on registrars and, with an "ICANN accredited" seal, inviting the public to rely on those terms for a secure domain name registration.

In cases where ICANN fails to recognize a registrar's problems, concerned members of the public should be entitled to take action themselves. As well as enforcing public-benefit obligations on its own, ICANN should facilitate individual action by removing the "no third-party beneficiary" language from its contracts.

In a welcome move of openness, C-SPAN has announced a liberalized copyright assertion policy:

C-SPAN is introducing a liberalized copyright policy for current, future, and past coverage of any official events sponsored by Congress and any federal agency-- about half of all programming offered on the C-SPAN television networks--which will allow non-commercial copying, sharing, and posting of C-SPAN video on the Internet, with attribution.

...

The new C-SPAN policy borrows from the approach to copyright known in the online community as "Creative Commons." Examples of events included under C-SPAN's new expanded policy include all congressional hearings and press briefings, federal agency hearings, and presidential events at the White House.

This seems much smarter than going after members of Congress for blogging the network's footage of Congressional hearings. C-SPAN often provides the only window into the workings of our government. Now, those windows are more clearly open.

Update: Thanks to Carl Malamud for publicly pressing C-SPAN to do the right thing here.

There's a difference between copyright assertion and copyright ownership. Like William Patry, I would have defended Speaker Pelosi's un-permissioned use of C-SPAN videos of Congressional hearings as non-infringing or as fair use. She, however, she chose to take them down and replace them (at some trouble or expense) with alternate videos from committee cameras in response to C-SPAN's assertion.

As Speaker Pelosi's story indicates, whether or not C-SPAN has a copyright in the minimal creativity of positioning cameras before a government hearing, its copyright claims prevented some people from using the streams. That chill operates as a law in itself, reducing the discourse around political events from what it could be if people felt secure in their non-infringing use of videos. C-SPAN's announcement can reduce the uncertainty. We need not concede that the videos are protected by copyright to welcome a promise not to assert copyright claims.

At least in this case, YouTube seems to be following the DMCA's notice-takedown-counter-repost dance. Fourteen business days (512(g)'s outer limit) from my counter-notification, I received this email from YouTube:

Dear Wendy,

In accordance with the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, we've completed processing your counter-notification regarding your video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4uC2H10uIo. This content has been restored and your account will not be penalized. For technical reasons, it may take a day for the video to be available again.

The NFL has apparently chosen not to sue to keep the video offline. Once again, therefore, viewers can see the NFL's copyright threats in all their glory.

I'm left wondering how many other fair users have gone through this process. On Chilling Effects we see many DMCA takedowns, some right and some wrong, but very few counter-notifications. Part of the problem is that the counter-notifier has to swear to much more than the original notifier. While NFL merely had to affirm that it was or was authorized to act on behalf of a rights-holder to take-down, I had to affirm in response that I had "good faith belief that the material was removed or disabled as a result of mistake or misidentification of the material to be removed or disabled." A non-lawyer might be chilled from making that statement, under penalty of perjury, even with a strong good faith belief.

Thanks for all the comments!

Teaching my privacy class about encryption provides a good reason to update my own encryption setup -- and it's nice to see that user-friendly encryption on the desktop has proceeded quite a bit.

First, replace an expired PGP (GnuPG) keypair,

First, replace an expired PGP (GnuPG) keypair, gpg --gen-key, and submit the new public key, fingerprint 456CAD51, to keyservers.

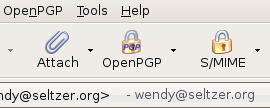

Plugins for Eudora never worked particularly well, so I'd been using gnupg on the command line, and not so frequently as I'd have liked. The Enigmail plugin for Thunderbird brings pushbutton email encryption and signature.

Finally, the self-signed SSL certificate for seltzer.org needed renewal (and its CA had moved from San Francisco to New York). Another 5 minutes and that was back up.

Maybe social norms and unease-of-use don't deter the use of encryption so much as they once did.