Newswires and other media were buzzing yesterday over the Justice Department's subpoena to Google for search terms and URLs. The buzz got louder when Judge Ware indicated in court that he was likely to order Google to respond, at least in part. (Londoners might have seen me interviewed on the BBC news.)

The story converged the public's interest in everything Google with concern about government spying and the erosion of privacy online -- even if little of that privacy was ever directly at issue here. The government asked for search terms and a selection of URLs, not the IP addresses that could most directly link terms to the users who searched for them; its stated purpose was not to investigate individuals but to gather pieces that would help DOJ defend the Child Online Protection Act, a prohibition on showing material "harmful to minors" that has been on constitutional hold since its enactment in 1998. Google opposed the request, saying it called for trade secrets, was unduly burdensome, and further, that it might chill some of the search engine's users.

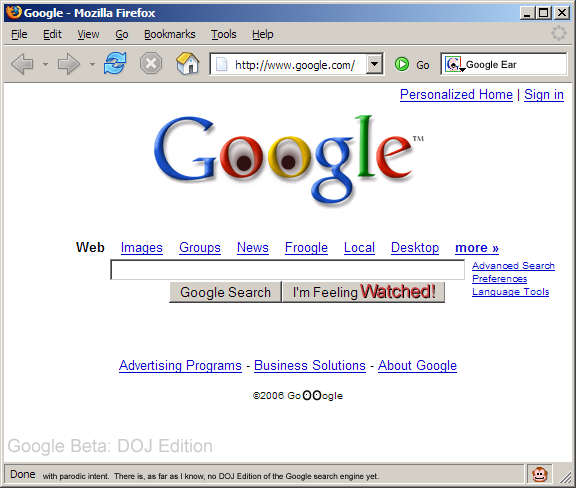

Even more than an actual privacy violation, the subpoena raised the preception of a privacy breach. News of the subpoena started many people thinking about how much of their personal lives they turn over to search engines -- and how little they know about what happens with that information next. With a government intent on listening to communications without warrants, could this subpoena be the first step toward a broader sweep of search engine records for other purposes? Our current privacy laws don't do a great job of protecting the information we turn over to third parties, such as search engines. Google could help protect privacy by keeping less data, but its business interests won't always align with its users' privacy wishes. The interest in the DOJ-Google subpoena shows we need to do better.

When a newspaper obtained records of then-Judge Bork's video rentals duringn 1987 hearings on his nomination for the Supreme Court, the public and members of Congress were similarly shocked that these records were so easily available. In response, Congress passed the Video Privacy Protection Act, prohibiting disclosure of video tape rental records without a warrant or court order. Though limited to sale or rental of "prerecorded video cassette tapes or similar audio visual materials," the VPPA stands out as one of our strongest privacy protection laws.

The DOJ's subpoenas for search records should be web searches' "Bork moment." Search engines, and our comfort in using them unobserved, are a key part of the Internet's vitality. If no current law protects us against government Googling our Google records, it's time to draft a law that does.

Posted by Wendy at March 15, 2006 08:39 AM | TrackBack