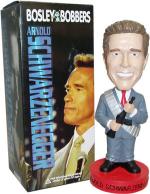

Counsel to Arnold Schwarzenegger sent a cease-and-desist letter threatening a lawsuit against the makers of a Schwarzenegger bobblehead doll. Seemingly oblivious to the fact that the Governor of California is a political public figure, the lawyers demand millions of dollars in compensatory and punitive damages for the "egregious and malicious" "use of Mr. Schwarzenegger's publicity rights."

Counsel to Arnold Schwarzenegger sent a cease-and-desist letter threatening a lawsuit against the makers of a Schwarzenegger bobblehead doll. Seemingly oblivious to the fact that the Governor of California is a political public figure, the lawyers demand millions of dollars in compensatory and punitive damages for the "egregious and malicious" "use of Mr. Schwarzenegger's publicity rights."

Best of all, though is the letter's conclusion:

This is a confidential legal notice and may not be published, in whole or in part. Any republishing or dissemination of same, including but not limited to the posting of the contents hereof on the Internet, shall constitute copyright infringement and will subject the re-publisher(s) to civil liability for such actions.You say infringement, I say fair use. Sorry, but I'm not chilled.

Among all the Google IPO hype, Pete Kaminski reminds us why Google is still cool -- they propose to raise $2.718281828 billion, the irrational, transcendental number e.

Thanks to Ernie for pointing out the latest from TrueMajority: a video mashup of NBC's The Apprentice with news footage of George W. Bush, in which Trump Fires Bush (mirrored flash or quicktime). Never mind Trump's trademark applications for "You're Fired", this could raise copyright issues too!

I think it's clear the mashup is a political parody that would be protected as fair use, but in the world of the broadcast flag, post July 2005, neither I nor a judge might ever get to make that call. If the "copy never" flag is set, commentators never get the raw materials for their parodies; judges never get to reset the bounds of fair use to an evolving media culture. The public's rights are frozen in 2004 while technology marches forward. That shouldn't be, since as the Canadian Supreme Court has said so well: "user rights are not just loopholes." (CCH Canadian Ltd. v. Law Society of Upper Canada)

When Brewster Kahle sees a problem, -- preferably a big, hairy, audacious problem -- he's likely to ask, without blinking, "Where do we start?" That's the approach he's taken to his (and our) current task, providing "universal access to all human knowledge."

Where most of us would be overwhelmed by the sheer size of the task, Brewster sees a challenge to be categorized and attacked systematically: Why can't we as a society share with all of our members the learning we've produced? What does that mean? Well, let's say there are 26 million books in the Library of Congress; 2-3 million sound recordings; maybe 100,000-200,000 theatrical releases and as many more video ephemera; 50 million websites; 1000 channels of television. For each chunk, the Internet Archive has a project: The Internet Bookmobile and million book project; live music archive; moving image collections; and, of course, the Wayback machine.

In his closing keynote for CFP, Brewster asked three questions about this universal access to all human knowledge: "can we?" "may we?" and "will we?" He expressed little doubt on the first -- technology can get us there if we have the will. As for the "may we?", to Brewster's credit, he's not willing to let the law block his vision. So he starts with public domain and permission-granted works, and builds. Perhaps that takes us to the point where the archives speak for themselves, begging to be filled first with orphan works, then classics, then ....

May we all share Brewster's will.

David Dill, Stanford Professor of Computer Science and Director of VerifiedVoting.org highlights key problems with electronic voting systems as states are currently implementing them. The machines are provably insecure, and don't give voters any opportunity to prove their accuracy. It's not enough just to clean up the code, Dill says -- we need to put outside checks into the system so voters can see that their votes are being counted (and re-counted) as cast. That's why EFF is working with Verified Voting to promote voter-verified paper ballots.

The CFP 2004 > Computers, Freedom & Privacy Conference kicks off today with tutorials, followed by a full schedule of panels and keynotes Tuesday through Friday in Berkeley. I'll be speaking Thursday about the recording industry's assault on Internet privacy and Friday about our Chilling Effects Clearinghouse.

Even if you can't be in Berkeley, there's a crowd of bloggers keeping notes, and thanks to freenode, an IRC channel #cfp: irc://freenode.net/cfp .

The New York Times runs a creative piece on Disney's aging mascot, Building a Better Mouse. As its writer tells Mickey's history, the Times has eight artists update the mouse's image for 2004: supermouse, hipster, and aging smoker among them. The article mentions the Sonny Bono copyright extension that keeps Mickey locked up beyond his 75th birthday, but doesn't discuss the copyright status of the illustrations -- fair use transformations or infringing/licensed derivatives? I'd go with the fair use, but would an independent artist or publisher without the backing of NYT-legal have similar confidence?

Audi and David Bowie are embracing the mash-up culture that brought us The Grey Album with a contest: remix two Bowie songs and put yourself in the running to win an Audi TT.

The buzz in the music business is all about mash-ups. You've read about them, you've heard them, now it's time to create your own. A mash-up is a song created from parts of other songs, "mashed-up." Mix and match songs to create something new. That's what you'll do here with any track from David Bowie's "Reality" CD and any other favorite Bowie track. Mix, match, mash-up and make something new.Audi even has a pretty cool commercial comparing their progress to that of publishing technology -- from calligraphic script, through movable type, to the web. Sad, then, that they don't seem willing to permit the song-mashers to share their creations beyond the contest. From the rules:

By entering the Contest, each entrant acknowledges and agrees that: (a) Sponsors are granting entrants a limited, non-exclusive license to use the Reality Masters and Bowie Masters in connection with, and solely as a part of, the Contest and then only for the duration of the Contest, (b) entrants shall have no right, title or interest in the Masters, and (c) any use of the Masters other than as permitted by these Official Rules will constitute a violation of the Contest Rules and may constitute copyright infringement.Copyright shouldn't have this lock on culture. It needs to evolve in step with the technology it regulates. (Aaron beat me to this one Copyfight)

My father, a great litigator, taught me the value of analogies and stories to good lawyering: The right story creates a context in which your arguments make sense. For the past quarter century, copyright law has been dominated by a property story. Little surprise, because those telling the story -- the publishers, broadcasters, and entertainment companies to whom we've delegated the maintenance of culture -- use it to consolidate their control. In a property story, stopping "theft" by any means necessary makes sense.

Lawrence Lessig gives us an alternative story, a story about Free Culture. Building upon the history Jessica Litman recounts in Digital Copyright, Lessig shows how copyright's extended term and expanded scope block creativity: Documentary filmmakers have to cede editorial decisions to lawyers because they won't get a showing if they rely on "fair use" for a few seconds of The Simpsons playing in the background; Programmers can't teach robotic dogs to dance.

In the free culture story, copyright exists to promote culture, and culture benefits from sharing. When copyright's controls impinge on public discussion and subsequent creativity, copyright should be changed, not the public "copying." Copyright law didn't descend from the heavens fixed in stone. It came to American law from a group of founders who were deeply skeptical of monopoly control but saw cultural value in granting authors short-term, limited-scope protection from commercial appropriation. In the founders' tradition, we should reshape copyright so it continues to promote cultural progress; updated for today, that means giving copyright holders less control, not more.

For Lessig's book, a Creative Commons license allowed the public to build a trove of remixes and new formats (see especially the audiobook). As more works are made available under CC and similar open licenses, we'll see local advantages, and brighter stories. Perhaps these will be enough to persuade the Disneys and Sonys to open their cultural dark archives. In the meantime, I hope that the freely share-able works, and the stories they tell, will inspire others to join our fight to change the copyright law.

I'm pleased to announce that as a consequence of EFF's merger with the U.S. Department of Justice, announced today, I won't have to move to Canada after all. Instead, we'll be able to influence the sound development of copyright law here in the U.S. Plus, since DOJ is the acquired party, it has renounced its traditional pre-merger investigatory role.